Raw feeding - BARF for dogs and cats - Part III: Problems and Risks and Case Studies

MedUP vetpool

Nadine Paßlack, Jürgen Zentek

BARF or raw feeding of dogs and cats is enjoying increasing popularity. This can be explained not least by the fact that many owners want their animals to be fed "naturally", based on the original diet of the dog or cat (BARF = "Bones And Raw Foods"). It is the task of the veterinarian to inform about possible risks and to give adequate hints for a sufficient energy and nutrient supply of the animal.

Part III of this article presents problems and risks of BARF feeding and Case studies.

Problems and risks

Mineral deficiencies and oversupplies

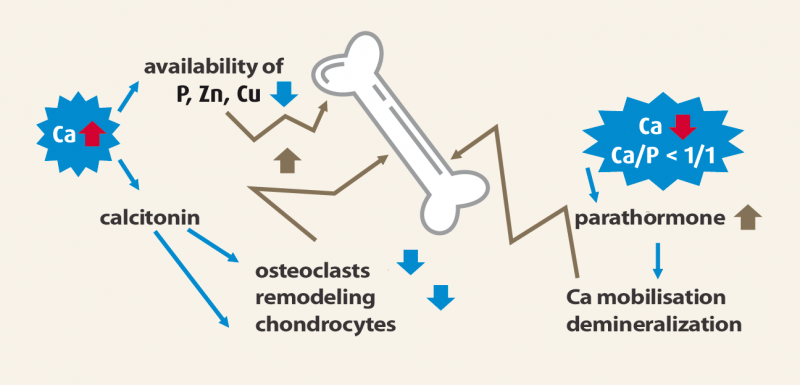

In the context of raw feeding, missupplies with minerals often occur in practice, as unsuitable feed materials and / or quantities of these are used. This can cause massive disturbances in dogs and cats. For example, an over- or undersupply of calcium is problematic and especially with large dog breeds there is the danger of serious skeletal disorders: In practice, calcium oversupply occurs either through the uncritical use of a mineral food or through the feeding of large amounts of bone. 1 g of bone per kg body mass per day is sufficient to meet the demand, but these values are often clearly exceeded in practical feeding. In addition to skeletal deformities, which can occur particularly during the growth phase, excessive amounts of bone can also lead to very hard faeces (so-called bone faeces) and subsequent constipations in the animals. Calcium deficiency occurs when no suitable mineral supplementation is carried out in a ration. As described above, meat is low in calcium and not suitable as the sole food to meet the nutritional requirements of a dog or cat. As a result of calcium deficiency, bone disorders (decalcifications) may also occur (Fig. 10).

Recently, the supply of iodine to dogs and cats within the framework of raw feeding has been increasingly critically questioned. It is generally known that iodine deficiency can impair thyroid function. However, a connection between the development of hyperthyroidism and the intake of excessive amounts of iodine (feeding of parts of the throat!) is currently being discussed. Köhler et al. (2012) investigated a total of 12 dogs with increased thyroxine concentrations in the plasma. All dogs were fed raw food and showed typical symptoms of hyperthyroidism like restlessness, weight loss, aggressiveness or tachycardia. Etiologically it was suspected that the feeding of throat parts increased the intake of exogenous thyroid hormones, which were not destroyed by gastric acid and thus resorbed in the intestine. The increased concentrations of exogenous thyroxine may then have caused the clinical symptoms. This theory was substantiated in the study in so far as the dogs did not show any clinical symptoms of hyperthyroidism after a feed change in which the feeding of pharynx was dispensed with and the thyroxine concentrations in the blood were again in the reference range. Against the background of this study, it seems reasonable in practice to inquire about and, if necessary, correct feeding in dogs and cats in the case of elevated thyroid levels. Finally it is pointed out that also by wrong supplies with other mineral materials problems can occur with dogs and cats. For example, a zinc deficiency can cause skin and fur problems.

Infections

The feeding of raw meat increases the risk of infection as pathogens cannot be inactivated by cooking. For example, parasite intermediate forms (tapeworm fins) that may be present in the slaughter by-products of ruminants are dangerous for the dog or cat. The intermediate parasite forms can be inactivated by cooking or storage at minus 18 -20 °C for at least 24 hours. Mouse dogs can take up the fox tapeworm, which is dangerous for humans, and excrete the eggs (danger of alveolar echinococcosis in humans). In cats, on the other hand, the development of E. multilocularis is inhibited and only a in a few cases eggs are excreted. In addition to exposure to parasites, bacterial contamination of raw meat can also lead to problems in dogs and cats as well as in some people living in the same household. For example, an infection with salmonella can be dangerous. Although the dog seems to tolerate the intake of Salmonella with the food quite well, the excretion of the bacteria carries a certain risk especially for children living in the household and elderly people. In addition, the dog can also develop symptoms of infection (especially diarrhoea). Various factors, such as the amount of salmonella ingested, the type of salmonella and, last but not least, the immune status of the dog play a decisive role.

Finally, the risk of infection with the Aujeszky's virus through the feeding of raw pork should be mentioned. If dogs or cats are infected with the virus, this infection is always fatal for the animals. Although Germany has been officially free from Aujeszky's disease in domestic pigs since 2003, it should be taken into account that pig meat can also be imported from countries that are not free from this disease. In addition, there are also reports in Germany that antibodies to Aujeszky's disease have been detected in wild boars. For the reasons mentioned above, the feeding of raw pork and wild boar meat to dogs and cats should be avoided.

Malfermentation/mis-colonisation of the intestine

Often, with one-sided nutrition of dogs and cats with meat or slaughter wastes, it comes to disturbances of the microbial colonization of the intestine and as a result to false fermentations in the small or large intestine. The background to this is that an excessive protein intake or an increased intake of protein that is difficult to digest (feed rich in connective tissue) leads to the protein not being digested sufficiently in the small intestine and thus larger amounts of undigested protein reaching the large intestine (Fig. 7). There, this nutrient influx leads to a one-sided promotion of certain protein-utilizing bacteria and thus to overall shifts in the composition of the intestinal microbiota. As a result, the animals can develop flatulence or diarrhoea. Against the background described above, one-sided meat feeding or the feeding of large quantities of slaughter waste rich in connective tissue in dogs and cats should be avoided.

Case studies

Case study 1

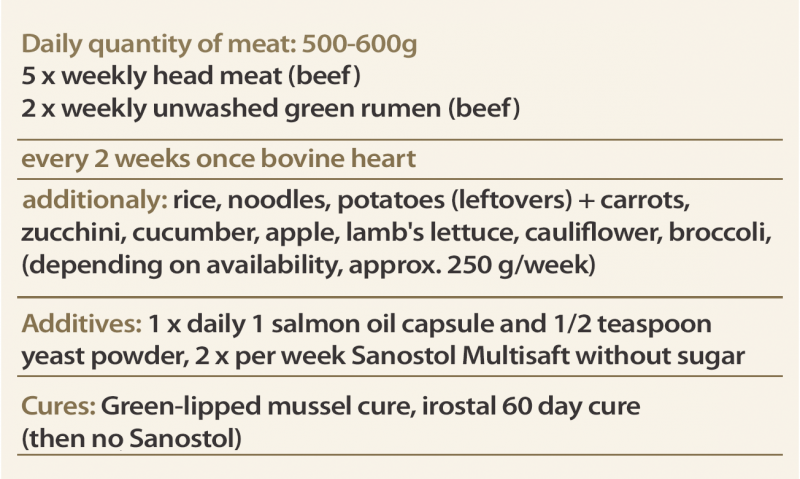

A dog owner wanted a ration check for her two French Bulldogs. This was an adult bitch (3 years, 14 kg body weight) as well as a still growing male (9 months, 10 kg body weight, final weight approx. 14 kg). The previous feeding of the two dogs is shown in Tab. 8.

The following aspects are conspicuous when looking at the previous feeding:

- There was no separate feeding of the two dogs. Thus the different needs of the young dog compared to an adult dog were not considered.

- Altogether it was a very protein-rich ration, since meat was fed predominantly. This could possibly lead to digestive problems in the dogs.

- The mineral supply seems insufficient.

(*The cases were collected as part of the "Advice on feeding pets and farm animals" of the Institute for Animal Nutrition at Freie Universität Berlin. No data on the patient owner are given.)

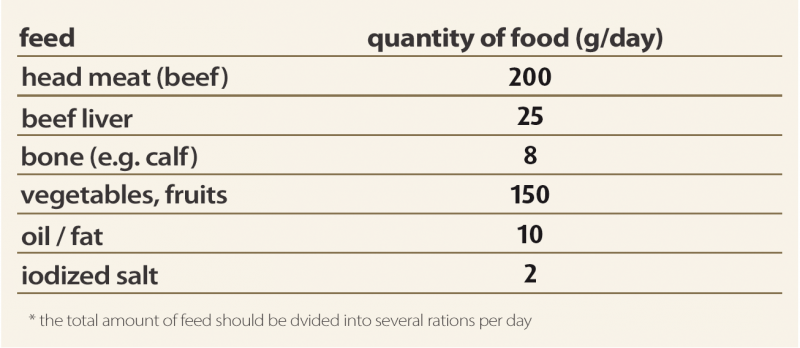

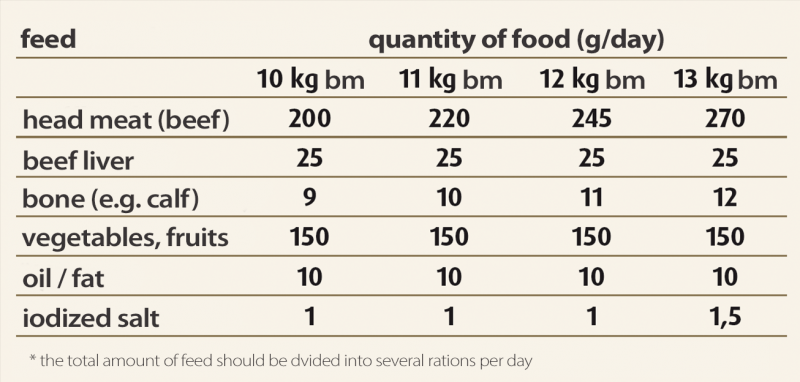

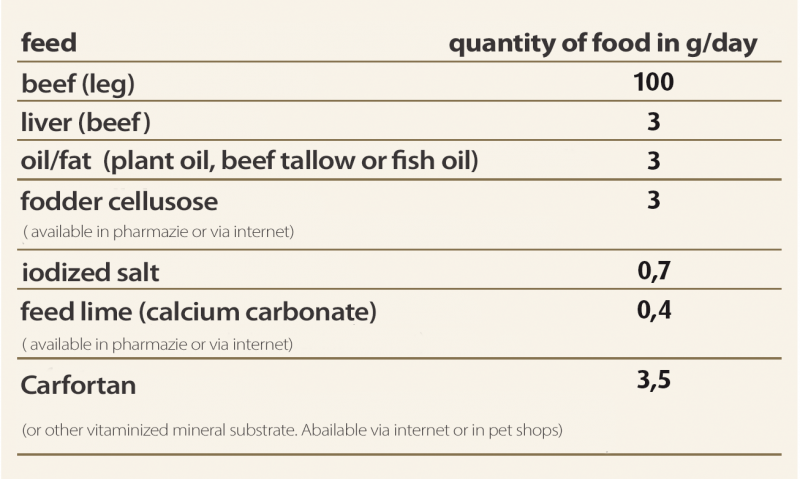

Accordingly, the owner was advised to feed the dogs separately until the end of their growth. The young dog's body weight should be checked regularly so that the ration can be adjusted if necessary. A constant supply of vitamins and minerals was also recommended. Tables 9 and 10 show the rations calculated for the two dogs. When looking at the feed quantities for the young dog, it becomes clear that, depending on the age, there is a different need for energy, protein and calcium.

Case study 2

A British Shorthair cat, 5 years, 4 kg body weight was introduced. The owner wanted a nutrition recommendation, whereby a 50 %ige or also 100 %ige raw feeding should take place. So far, Vet-Concept has fed approx. 100 g of a wet food and approx. 15-20 g of a dry food daily, distributed over three meals. The owner replaced two meals a week with raw meat (or reduced the quantities of wet and dry food on these days). Pure muscle meat from lamb, beef, chicken or turkey was used.

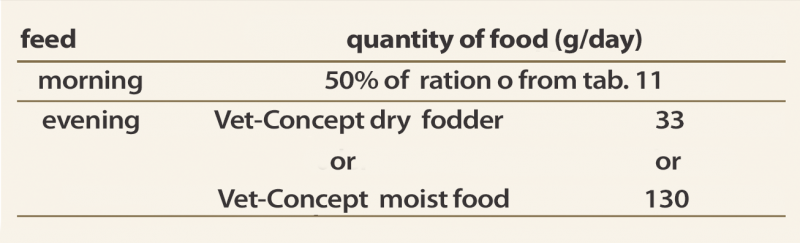

In accordance with the cat owner's wishes, a ration consisting of 100 % and 50 % of self-compiled feed was calculated. In the latter case, a combination with a commercial product from the company Vet-Concept was used (Tables 11 and 12).

Literature

Benno, Y., Nakao, H., Uchida, K., Mitsuoka, T. (1992). Impact of the advances in age on the gastrointestinal microflora of beagle dogs. J Vet Med Sci 54, 703-706.

Köhler, B., Stengel, C., Neiger, R. (2012). Dietary hyperthyroidism in dogs. J Small Anim Pract 53, 182-184.

Meyer, H., Kienzle, E., Zentek, J. (1993). Body size and relative weights of gastrointestinal tract and liver in dogs. J Vet Nutr 2, 31-35.

Meyer, H., Zentek, J., Habernoll, H., Maskel, I. (1999). Digestibility and compatibility of mixed diets and faecal consistency in different breeds of dogs. J Vet Med A 46, 155-165.

Meyer, H., Zentek, J. (2010). Ernährung des Hundes. Grundlagen – Fütterung – Diätetik. Parey Verlag, Stuttgart.

Opitz, B. (1996). Untersuchungen zur Energiebewertung von Futtermitteln für Hund und Katze. Diss Med Vet, München

Zentek, J. (2012). Hunde richtig füttern. Eugen Ulmer GmbH & Co., Stuttgart (Hohenheim).

Teaser image credits

joshua-j-cotten, unsplash